First published in International Aquafeed, January-February 2015

From ‘boom or bust’ for key species groups of shrimp, salmon and tilapia!

Australian aquaculture is in many ways at the crossroads. It clearly has potential but regrettably there are many things holding it back. Much of Australia has been based on the ‘boom or bust’ process and aquaculture is very much in that zone.

Australian aquaculture is in many ways at the crossroads. It clearly has potential but regrettably there are many things holding it back. Much of Australia has been based on the ‘boom or bust’ process and aquaculture is very much in that zone.

Setting the scene

First, we have to understand and accept that Australia is seafood deficient and already relies on imported seafood for around 75 percent of all seafood consumed. This has long been the case despite Australia having the world’s third largest Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) at around 10 million square kilometers. When you compare that with the size of the Australian mainland States and Territories, which is 7.69 million square kilometers, you can appreciate the size.

Australia is surrounded by both tropical and by temperate seas, but these waters are not particularly bountiful as far as wild fish are concerned and there are many scientific and geographic explanations for this.

However, we must ask the question “has Australia really made the best uses of its water resources or have they been, so far, wasted by not embracing aquaculture, the world’s fastest growing primary industry?”

Reports that point to optimism

A Report was done on Imported Seafood by the Fisheries Research & Development Corporation (FRDC) and detailed analysis of fisheries statistics, various reports and trade information from around Australia, revealed that:

- The 193,000 tonnes of seafood imported in financial year 2008/09, some 250 species/ products from aquaculture and wild-catch fisheries, had a landed cost of Aus$1.3 billion and an estimated final sales value of Aus$4.5 billion

- The business activities transacted in importing this seafood, from the landing port to the consumer’s plate added Aus$3.2 billion (4.5 minus 1.3 billion) to the Australian economy

- Almost all the imported seafood was used for seafood consumption through the retail and the food service sectors

- This quantity provided 72 percent of the fish and shellfish flesh consumed in Australia and underpinned more than two-thirds of Australia’s employment in the seafood post-harvest sector

- Canned fish, frozen fillets, frozen whole and processed prawns and frozen squid products were the major imported items

A few months ago, Rabobank gave a view that the strong thematic drivers, both local and global, are critical to the current growth in the industry advising that these will continue to support further growth in the medium to long term.

They went on to give the view that the rate of growth and outlook varies significantly across sectors, depending on the exposure to the key growth drivers and suggested that in order for Australian seafood sectors to grow and remain competitive, it is important that strategies are developed to the address the following:

• Ability to sustainably increase production

• Technological and aquaculture improvements

• Market concentration, with high barriers to entry

• Brand development and reputation

• Improving market access

• Opportunities and challenges with meeting Asian demand growth

• Supply chain partnerships

• A competitive value proposition relative to alternate proteins

Rabobank concluded that the overall the outlook remains very optimistic across most key Australian sectors.

However, there will be challenges, particularly with regard to managing environmental and sustainability issues, biosecurity as well as trade flows.

Import reliance creates its own issues

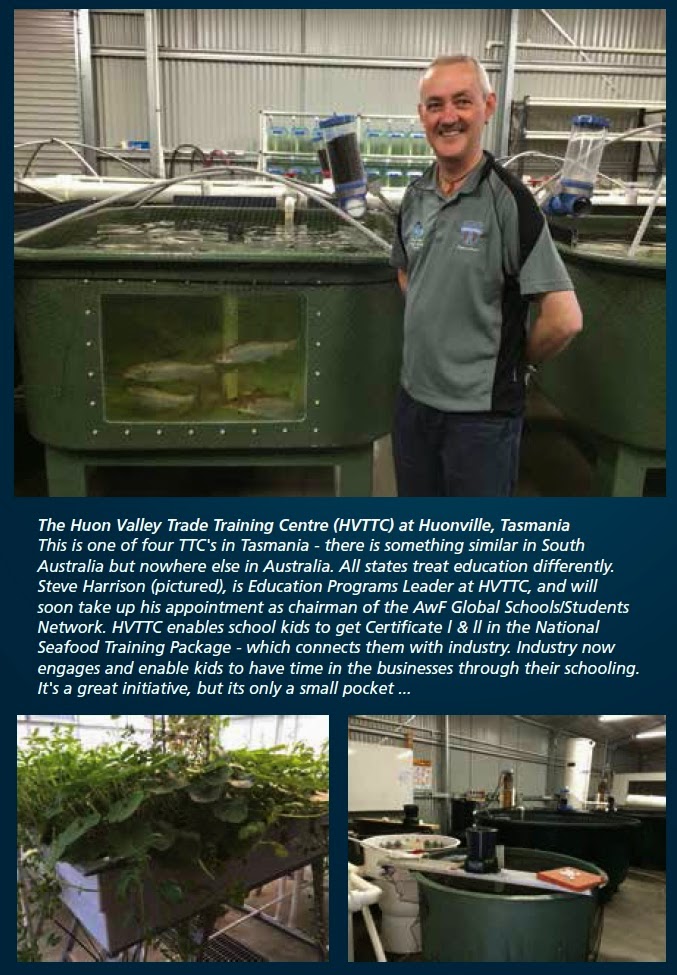

There is more to this as there are added issues to being import reliant, these include price variances due to market forces and exchange rates. Trained staff are not that easy to come by and what is an enigma is that whilst Australia has an excellent Seafood Training Package it is used sparingly.

The aquaculture industry in Tasmania has definitely made the most of this but other states are lacking a training focus. Clearly if you are not training your staff there will be consequences down the track.

Most countries in Asia that Australia relies on for seafood are not only large consumers of seafood themselves but are also expecting massive increases in their middle classes. It is understood that as people move to middle class status their food consumption patterns change and they eat more protein, especially proteins which they already enjoy, e.g. seafood.

This increase in middle classes is actually a potential double hit for seafood consumers in Australia. As demand rises in those countries they will not only seek to eat more of their own production but will also be keen to import ‘special’ niche products – exactly the area where Australian production could fit.

The aim of Australian seafood harvesters and processors generally is always at export markets rather than domestic markets, it has been part of the country’s psyche for generations.

This further acerbates the supply position and whilst you would think with the abundance of resources, technology, science and education that Australia has, we would see the country wallowing in opportunities. Alas, Australia seems to be paralysed and has been that way for some time.

Politicians rarely understand the dynamic of seafood and regrettably politics has played a large role in Australia’s current position. Some say that Australia has not moved into the new dynamic of aquaculture as well as it should have, especially in the governance arena.

No cohesive plan for shrimp, salmon or tilapia

There is no ‘one plan’ for Aquaculture and with nothing happening in Commonwealth waters it is the States/Territories that rule the roost. Governance is complicated and tied up in red and green tape.

There are no two states with the same legislation/regulations. In most states/territories fishing, a hunter-gather approach to harvesting, is still locked with aquaculture, and that would seem to confuse and obstruct opportunities. When you hear stories of no new aquaculture licenses issued in a state for over a decade when the rest of world is embracing aquaculture it sends out bad messages to the industry and potential investors.

Australia does have excellent science, research and education. This is highlighted by CSIRO Australia, who, after 10 years of research, have perfected the Novacq™ prawn feed additive.

Farmed prawns fed with Novacq grow on average 30 percent faster, are healthier and can be produced with no fish products in their diet, a world-first achievement in sustainability.

Having this advantage is a major plus in the market but alas the volumes that are produced in Australia are negligible. The quantity of farmed prawns produced in Australia is only around 4500 tonnes whereas in Indonesia and many other similar countries they are producing over 300,000 tonnes – the quantities all over Asia certainly dwarf Australia’s activities.

At the moment for prawn Australia relies more on wild-catch product (and imports), with production stable at approximately 20,000 tonnes. When compared to the global supply of over six million tonnes, which is produced in approximately equal amounts by wild-catch and aquaculture, Australia is a minor producer, but this could potentially change in the future.

Whether a pipe dream or reality there is currently a project by Australia’s largest prawn farmer Seafarms Group Limited (itself a recently-acquired subsidiary of ASX-listed Commodities Group Limited), to create the world’s largest prawn farm.

Based in the remote north of Western Australia and aiming to create a 10,000ha Black Tiger Prawn, P. monodon farm. Whilst it is still early days and many uncertainties remain, if this farm was developed it could become one of Australia’s largest aquaculture sectors, potentially even surpassing salmon aquaculture in value terms. It would also place Australia among the top 10 largest global prawn producers and also making it one of the leading exporters.

Natural biosecurity a key advantage

Experts say from a land and feed availability perspective and given the suitable climate in this region, the farm should be feasible. The high level of biosecurity in Australia would be a great advantage, especially as the global prawn sector has been through some crises with the outbreak of Early Morality Syndrome, which decimated key production regions such as China and Thailand and pushed global prices to new highs.

Talking of biosecurity. It is important to note that imported prawns in Australia are only allowed if they are approved through Biosecurity Australia.

Biosecurity Australia completed the final import risk analysis (IRA) report and strict policy recommendations for the importation of prawns and prawn products from all countries have been in place for over five years.

The final IRA report recommended risk management for white spot syndrome virus (WSSV), yellowhead virus (YHV), Taura syndrome virus (TSV) and NHPB (in the case of unfrozen product) to meet Australia’s appropriate level of quarantine protection.

The IRA recommends that imported prawns be sourced from a country or zone that is recognised by Australia to be free of WSSV, YHV, TSV and NHPB (the last disease agent, for unfrozen product only); or have the head and shell removed (except for the last shell segment and tail fans) and, if not from a disease free source, have each batch tested on arrival with negative results for WSSV, and YHV; or be ‘highly processed’, that is head and shell-off (except for the last shell segment and tail fans), and coated for human consumption by being breaded or battered, marinated in a wet or dry marinade, marinated and placed on skewers or processed into dumpling, spring roll, samosa, roll, ball or dim sum-type product; or be cooked to a standard where all protein is coagulated and no uncooked meat remains.

Of course biosecurity is important but tens of thousands of tonnes of imported green prawns have been imported to Australia - over the past 50 years - without any major issue. Strangely with such rules no one seems to take in the costs to consumers.

Salmon - the one bright light

Australia’s bright light in aquaculture is in Atlantic Salmon, clearly not an indigenous fish, but one which has now cemented itself strongly in Tasmania. The volume is heading towards 60,000 tonnes (Australia’s largest single species harvest) with the majority of the product aimed at the domestic market and with strong environmental credentials being obtained and continually chased.

It is clearly an industry sector which stands out above most others in Australia. When you consider that the harvest started in 1986/87 with a harvest of 53 tonnes you can appreciate the growth.

Tassal Limited is the largest producer of salmon in Tasmania, with almost eight million Atlantic salmon growing in cages that can each hold up to 40,000 fish.

Head of sustainability for Tassal, Linda Sams has been reported as saying “The Company needs to expand to keep up with demand. By 2030 we talk about doubling our production, but there's a number of ways we'll do that.

“We'll do that through actually growing more fish, but we'll actually do that as well by growing fish more efficiently."

But Tassal and the other major Tasmanian Salmon farms of Huon Aquaculture and Petuna, who would jointly be close to being Tasmania’s largest employers, are continually fought on expansion by two groups.

Yes, you would expect in Tasmania, where the Green lobby gets most of its strength in Australia, that the environmentalists would be heavy objectors but it is also quite fascinating that another seafood group, the rival abalone industry, are also wanting the expansion stopped. Both accuse salmon farms of polluting Tasmania's waterways and killing off marine life.

In Victoria, Pacific Oysters are considered noxious pests and are not allowed yet South Australia, Tasmania and NSW have created viable businesses. Talking of noxious pests Australia has spent millions of dollars trying to find the ‘silver bullet’ for European Carp and Tilapia (the two largest aquaculture species in the world) as against using the research and technical knowhow on how to grow such species and satisfy market demand for cheaper fresh fish.

Yet Atlantic Salmon and fish like Rainbow Trout are allowed and even grown by Government hatcheries.

We have not broached the money spent on species like Tuna, Murray Cod and Silver Perch or the Seafood CRC, so you can see Australia is a confusing mix. Until there is some political leadership and a national plan which includes engagement with all States/Territories creating a more investor-friendly environment, then it should expect the boom or bust era to continue and for the reliance on imports to get stronger.

Read the magazine HERE.

The Aquaculturists

This blog is maintained by The Aquaculturists staff and is supported by the

magazine International Aquafeed which is published by Perendale Publishers Ltd

For additional daily news from aquaculture around the world: aquaculture-news

No comments:

Post a Comment