by Lian Heinhuis, Analyst Seafood, Food

& Agribusiness Research and Advisory, Rabobank International, The

Netherlands and Gorjan Nikolik, Rabobank International, Singapore

Global tilapia production volumes have

increased from just over 100,000 tonnes in 1980 to 4.5 million tonnes in 2012,

and the industry has an estimated total value of US$6.7 billion.1 The export

market is currently dominated by China, while the United States (US) is the

biggest importer. In the coming years, we expect China to focus more on its

domestic market, which will create opportunities for other producers to emerge

and increasingly supply growing markets, including the US.

Latin American producers are in a strong

position to benefit due to their location, access to feed and natural

resources. Having already doubled output between 2007 and 2012, the region is

expected to see further growth.

Tilapia is

thriving thanks to biology and technology

The whitefish sector has seen incredible

growth rates in past years.

Tilapia is farmed in small backyard farms

as well as industrial compounds managed by multinational companies. Production

methods range from simple cage systems to complex indoor recirculation

facilities. Technology has played an important role in the development of the

tilapia industry, and innovations such as the sex-reversal technology that

allows farmers to grow only the faster-growing male fish have greatly

contributed to better farming practices and output.

Tilapia is farmed in small backyard farms

as well as industrial compounds managed by multinational companies. Production

methods range from simple cage systems to complex indoor recirculation

facilities. Technology has played an important role in the development of the

tilapia industry, and innovations such as the sex-reversal technology that

allows farmers to grow only the faster-growing male fish have greatly

contributed to better farming practices and output.

The main tilapia-producing country is

China, which accounts for a third of all production (1.5 million tonnes

annually).

Chinese government programmes on

farming—along with support subsidies and programmes focused on advancing

technology and genetics—have resulted in a growing tilapia industry.

Family-owned farms account for the largest share of production.

Although volumes from China are larger than

volumes from any other country, profit margins have been very low, and the

industry as a whole has been making a loss.

Subsidies have created competitive prices

for the Chinese product, which is sold as frozen fillets in the US (almost half

of total Chinese tilapia exports).

However, they also pose a risk, as

discontinuity could mean rising costs. Volumes in the global tilapia industry

have seen strong growth, and—assuming no major disease outbreak or other

negative event occurs—there is potential to double output again to nine million

tonnes (live weight equivalent) by 2025 (see Figure 2).

Tilapia is

America’s next top seafood item

Tilapia is

America’s next top seafood item

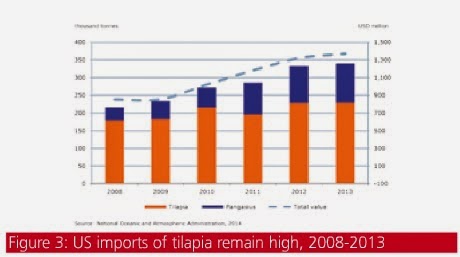

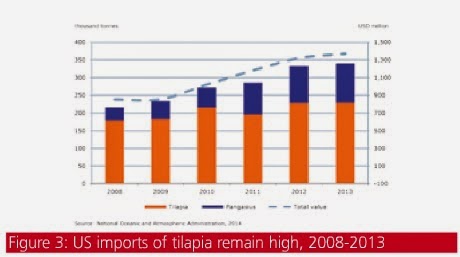

The US is the most important market for tilapia. With import volumes of more than 228,000 tonnes (over 600,000 tonnes in live weight equivalent), Americans consume more than other major tilapia-eating countries such as Egypt or China (see Figure 3).

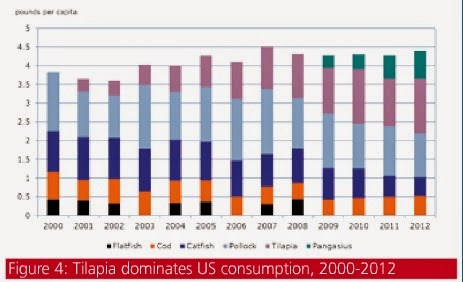

Tilapia has risen fast on the charts of

seafood popularity and now only trails salmon, shrimp and tuna as the most

favoured seafood item in the US.

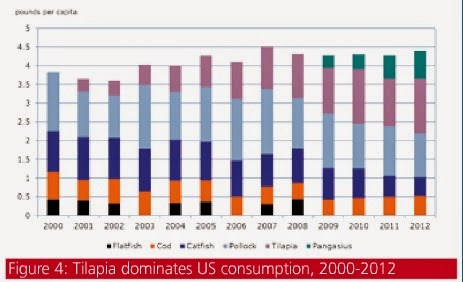

While originally presented as a low-cost

alternative for wild-caught whitefish, the product is now consumed more than

cod or pollock, and it dominates the broader whitefish category (see Figure 4).

As tilapia is still priced considerably higher than chicken (on average double

the price of chicken breast fillet), it is more relevant to compare it with

other seafood products.

However, in the longer term, this can also

have an impact on the consumption of species in the broader animal protein

segment—particularly on chicken—because of its similar neutral taste.

Tilapia is not as popular in Europe as in

the US. With frozen tilapia fillet imports of only 19,000 tonnes in 2013 -

barely 12 percent of US frozen fillet imports - the fish has not taken off

anywhere near like it has across the Atlantic.

Pangasius has established a much stronger

position than tilapia in Europe, with frozen fillet imports of 142,000 tonnes

in 2013. This can be explained by lower prices and tilapia producers focusing

less on this region - so far.

In the years to come, freshwater whitefish

consumption will continue to rise in the US. The focus on healthier diets will

increase demand of both tilapia and pangasius.

In the years to come, freshwater whitefish

consumption will continue to rise in the US. The focus on healthier diets will

increase demand of both tilapia and pangasius.

Since 2011, the popularity of pangasius has

declined somewhat, after bad publicity surrounding alleged poor farming

standards in Vietnam.

China’s position faces challenges

Asian producers - particularly China - have

dominated the global tilapia industry in the past decades. With a share of

nearly 74 percent in the US frozen fillet market and continuing growth (five

percent CAGR between 2008 and 2013), China is in a strong position.

However, there are reasons to expect the

Chinese product to become less competitive over time, including rising input

costs, currency, climate, limited resources and food safety.

Input costs are driven up by rising feed

and labour costs. This means that the product will become more expensive to

produce. Average labour costs in China more than doubled in the period between

2007 and 2012.

In past years, average retail prices of

pellet feed increased from RMB3260/tonne in 2006 to RMB4140/tonne in 2012.4

In past years, average retail prices of

pellet feed increased from RMB3260/tonne in 2006 to RMB4140/tonne in 2012.4

China has limited resources of fresh and

clean water. Pollution is an important problem, and there is increased

competition for water space from other agricultural and aquacultural products

such as rice and shrimp.

Food safety issues surrounding the Chinese

product have resulted in more negative market perception in the US, allowing

non-Chinese products to be sold for US$1/pound more. If this image problem

continues, Chinese frozen fillets could also become less popular.

Moreover, climate is an issue as tilapia

need water temperatures of at least 27°C, and the consistent conditions found

in more tropical areas of the world do not exist in China.

As the Chinese industry now heavily relies

on subsidies to produce at low cost, changes in policy could have another

negative impact.

As the Chinese industry now heavily relies

on subsidies to produce at low cost, changes in policy could have another

negative impact.

Combined, this could result in China

exporting less tilapia and being forced to develop its domestic market. Tilapia

sales in China are now mainly concentrated in the provinces where it is

produced and where it competes with traditional food fish such as carp.

Strong regional cultural traditions in the

Chinese diet make the country a difficult market to develop. Tilapia in China

has the most potential as a fillet, predominantly sold through retailers,

especially in the country’s south where people live close to the farms. The

live/fresh market is more difficult to enter, as people will first choose to

purchase traditional fish.

The other major challenge to Chinese

dominance of the farmed whitefish export market is pangasius. Imports of

Vietnamese pangasius - at a lower price per kilogramme (about 25 percent less)

- are growing faster than those of Chinese tilapia and pangasius exports to the

US between 2008 and 2012 were much higher than tilapia volumes from Latin

America, showing increasing demand for pangasius.

Vietnam currently produces around one

million tonnes of pangasius per year, and the government is supporting the

sector and has set a goal to expand it by 20 percent, to 1.2 million tonnes in

2015.

Furthermore, there is a good possibility

that other countries, such as Indonesia and India, will start large-scale

production of pangasius. The fish is perceived to be very similar to tilapia,

although its fillet colour is much whiter. Low prices and increased marketing

efforts could lead American consumers to increasingly choose pangasius,

although tilapia still has a distinct first-mover advantage and much wider

recognition among consumers.

Opportunities lie in other parts of the

world

The challenges create room for other

producers to become both exporters and more self-sufficient.

Mexico, for instance, is now a big importer

of tilapia, as it produces 70,000 tonnes, while consuming 130,000 tonnes. The remaining

60,000 tonnes are imported from China. Mexico has good production facilities

and capabilities of its own, but farmers there have found it difficult to

compete with Chinese prices, which have been about 30 percent lower than

Mexican tilapia prices.

In Africa, we can also expect further

investment in fish farming industries in order to meet local demand. Ghana is a

good example of this: the country has witnessed growth rates that have averaged

39 percent annually over the past five years. This comes from a very low base,

with production volumes of 26,000 tonnes in 2012. Local demand has been

increasing, and there are many initiatives to use small-scale fish farming of

tilapia as a way to alleviate poverty.

The key consumer and producer in Africa is

Egypt, which is the second-largest producer worldwide, with 768,000 tonnes in

2012, and growing rapidly by 15 percent per year (based on the CAGR between

2008 and 2012).

Other Asian producers such as India,

Thailand and Malaysia are also growing (albeit from a low base) and have export

potential.

Indonesia is already a sizable exporter to

the US, with 11,000 tonnes of exports in 2013 (from 717,000 tonnes total

production) and the unique position of being the only Asian country that sells

a high-value product, produced at high-quality standards (see Figure 5). The

country is also home to the largest production facility of the world’s leading

tilapia-producing company, Regal Springs.

Latin America is poised to take a bite out of the market

There are several factors putting Latin

American producers in a good position to obtain a bigger share of the

international tilapia market: the region has lower feed costs (soymeal prices

in Brazil are below prices in China, with an average difference of 11 percent since

2010); labour costs are increasingly competitive compared to China; the region

is close to the current key consumer market; the climate is right; and both

freshwater and brackish water resources are sufficient.

In 2012, Latin America produced only 453,000

tonnes of tilapia, which makes up about 10 percent of global production.

Although this is only a fraction of Asian production, there is good potential

for growth. In recent years, the tilapia industry in Latin America has already

shown strong growth rates, doubling in size from 2007 to 2012 - and exports to

the US are increasing. The Latin American tilapia product is sold fresh in the

US, for a premium price (about US$1/pound higher than frozen).

To grow the industry, Latin American

auxiliary businesses such as processing, feed and logistics will need further

development.

Rabobank projects Latin American tilapia

volumes could rise to at least two million tonnes by 2025, with more than half

of future production in this region expected to come from Brazil. The country

is already the largest Latin American producer and is especially resource-rich.

Countries such as Mexico and Colombia are also expected to strongly increase

production.

However, in some countries tilapia is

facing competition from other species, as is the case in Ecuador. Due to high

prices in the shrimp sector (due to a disease in Asia and Mexico), many

Ecuadorian farmers have left the tilapia business to pursue shrimp farming,

resulting in a decline of exports.

In conclusion

The tilapia industry has shown incredible

growth rates. In all production regions, volumes at least doubled in the period

from 2007 to 2012.

Of course, biological risks are always

present in any type of farming, and climate change or disease outbreaks could

seriously harm the industry, setting back production volumes.

Moreover, tilapia requires a relatively low

investment in the farm structure. Due to low-cost feed, it has a competitive

price point in both developed and developing markets. Tilapia are resilient,

they grow fast and are increasingly popular among consumers. The current

leading consumer market in the US is far from saturated, and consumption in

local markets is also expected to increase.

While China will remain a key producer in

the foreseeable future, Latin American producers like Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador

and Mexico are well positioned to produce high volumes that could supply both

domestic and international markets.

Other Asian producers such as Thailand,

Indonesia, India and Malaysia are also expected to strongly increase tilapia

output in the coming decades.

Although no fish-farming business is

risk-free, the future for tilapia looks bright.

As a source of affordable animal protein,

tilapia could (continue to) feed the masses and become a key commodity in the

animal protein market. What chicken has been for the poultry industry, tilapia

can be for aquaculture.

Low-cost feed, simple farming structures and fast growth contribute to its popularity among farmers, while its neutral taste makes it popular among consumers - characteristics that make it much like its terrestrial equivalent, the chicken.

The aquatic chicken industry will continue

to rise, which will bring some interesting new business opportunities for

farmers, but also for companies in secondary industries such as feed and

processing.

Read the magazine HERE.

First published in Internatiional Aquafeed, January - February 2015

Worldwide demand for seafood is growing and

wild catch production cannot grow at the same pace, meaning that aquaculture is

becoming key for the supply of aquatic protein. As the farming of

fish—especially freshwater species—rapidly gains popularity around the world,

opportunities increase for both farmers and players active in auxiliary

industries.

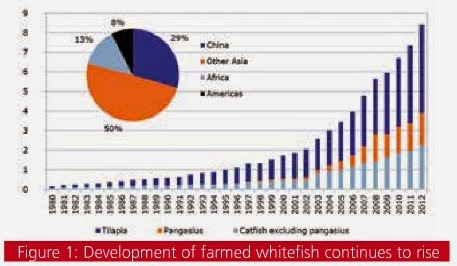

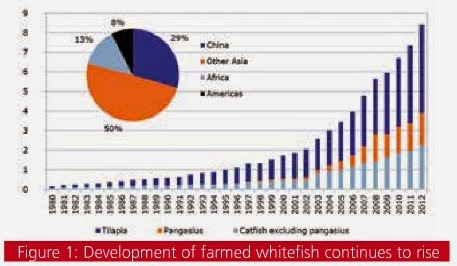

Farmed freshwater fish species, consisting

of different types of carp, catfish and tilapia, accounted for over half of the

66 million tonnes of fish produced in aquaculture in 2012 (see Figure 1).

Although carp is by far the largest subgroup

(38 percent of total aquaculture production), it is predominantly consumed

locally around the world. Like tilapia, pangasius has an export market and is

popular among western consumers; yet its market share is still relatively

small. Unlike the other species, tilapia has seen the greatest growth in

production and widespread appeal in global marketTilapia is easy to farm and feed and has a

neutral flavour that appeals to many, hence it is often compared to chicken.

Tilapia is one of the main drivers of this

growth, with farming having expanded to more than 80 countries and global

production volumes having grown by an average of 11 percent per year.

Tilapia is farmed in small backyard farms

as well as industrial compounds managed by multinational companies. Production

methods range from simple cage systems to complex indoor recirculation

facilities. Technology has played an important role in the development of the

tilapia industry, and innovations such as the sex-reversal technology that

allows farmers to grow only the faster-growing male fish have greatly

contributed to better farming practices and output.

Tilapia is farmed in small backyard farms

as well as industrial compounds managed by multinational companies. Production

methods range from simple cage systems to complex indoor recirculation

facilities. Technology has played an important role in the development of the

tilapia industry, and innovations such as the sex-reversal technology that

allows farmers to grow only the faster-growing male fish have greatly

contributed to better farming practices and output.

In addition, tilapia’s biological characteristics

provide further advantages to farmers worldwide: the fish is relatively

resilient, has a low-cost diet, needs little dissolved oxygen in the water and

reaches marketable size quickly.

Tilapia is

America’s next top seafood item

Tilapia is

America’s next top seafood itemThe US is the most important market for tilapia. With import volumes of more than 228,000 tonnes (over 600,000 tonnes in live weight equivalent), Americans consume more than other major tilapia-eating countries such as Egypt or China (see Figure 3).

In the years to come, freshwater whitefish

consumption will continue to rise in the US. The focus on healthier diets will

increase demand of both tilapia and pangasius.

In the years to come, freshwater whitefish

consumption will continue to rise in the US. The focus on healthier diets will

increase demand of both tilapia and pangasius.

However, these characteristics are

currently not exploited in marketing campaigns, with low price remaining the

key selling point. European consumption growth will be more challenging, as

farmed fish production has received some very negative media attention lately.

In past years, average retail prices of

pellet feed increased from RMB3260/tonne in 2006 to RMB4140/tonne in 2012.4

In past years, average retail prices of

pellet feed increased from RMB3260/tonne in 2006 to RMB4140/tonne in 2012.4

The currency will not benefit Chinese

competitiveness, with the yuan having appreciated by 24 percent since 2005, to

CNY6.14 per US$ in 2014.5

These issues present a scenario of increasingly

challenged competitiveness.

As the Chinese industry now heavily relies

on subsidies to produce at low cost, changes in policy could have another

negative impact.

As the Chinese industry now heavily relies

on subsidies to produce at low cost, changes in policy could have another

negative impact.

Nevertheless, the characteristics of the

industry provide cause for optimism. Tilapia is amongst the easiest fish to

farm, and - at least to date - no global disease outbreaks have occurred.

Low-cost feed, simple farming structures and fast growth contribute to its popularity among farmers, while its neutral taste makes it popular among consumers - characteristics that make it much like its terrestrial equivalent, the chicken.

Read the magazine HERE.

The Aquaculturists

This blog is maintained by The Aquaculturists staff and is supported by the

magazine International Aquafeed which is published by Perendale Publishers Ltd

For additional daily news from aquaculture around the world: aquaculture-news

No comments:

Post a Comment